The Fourier Transform (FT) decomposes a function of time (a signal) into the frequencies that make it up, in a way similar to how a musical chord can be expressed as the frequencies (or pitches) of its constituent notes.

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) converts a finite sequence of equally-spaced samples of a function into a same-length sequence of equally-spaced samples of the discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT), which is a complex-valued function of frequency. The interval at which the DTFT is sampled is the reciprocal of the duration of the input sequence. An inverse DFT is a Fourier series, using the DTFT samples as coefficients of complex sinusoids at the corresponding DTFT frequencies. It has the same sample-values as the original input sequence. The DFT is therefore said to be a frequency domain representation of the original input sequence. If the original sequence spans all the non-zero values of a function, its DTFT is continuous (and periodic), and the DFT provides discrete samples of one cycle. If the original sequence is one cycle of a periodic function, the DFT provides all the non-zero values of one DTFT cycle.

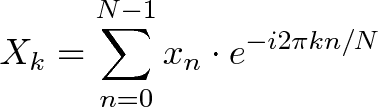

The Discrete Fourier transform transforms a sequence of N complex numbers:

{xn} = x0, x1, x2 ..., xN-1

into another sequence of complex numbers:

{Xk} = X0, X1, X2 ..., XN-1

which is defined by:

The Discrete-Time Fourier Transform (DTFT) is a form of Fourier analysis that is applicable to the uniformly-spaced samples of a continuous function. The term discrete-time refers to the fact that the transform operates on discrete data (samples) whose interval often has units of time. From only the samples, it produces a function of frequency that is a periodic summation of the continuous Fourier transform of the original continuous function.

A Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is an algorithm that samples a signal over a period of time (or space) and divides it into its frequency components. These components are single sinusoidal oscillations at distinct frequencies each with their own amplitude and phase.

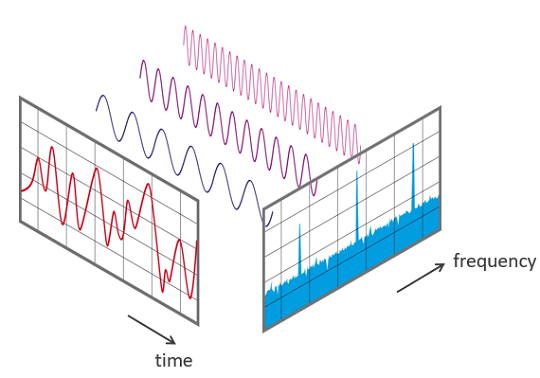

This transformation is illustrated in Diagram below. Over the time period measured in the diagram, the signal contains 3 distinct dominant frequencies.

View of a signal in the time and frequency domain:

An FFT algorithm computes the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of a sequence, or its inverse (IFFT). Fourier analysis converts a signal from its original domain to a representation in the frequency domain and vice versa. An FFT rapidly computes such transformations by factorizing the DFT matrix into a product of sparse (mostly zero) factors. As a result, it manages to reduce the complexity of computing the DFT from O(n2), which arises if one simply applies the definition of DFT, to O(n log n), where n is the data size.

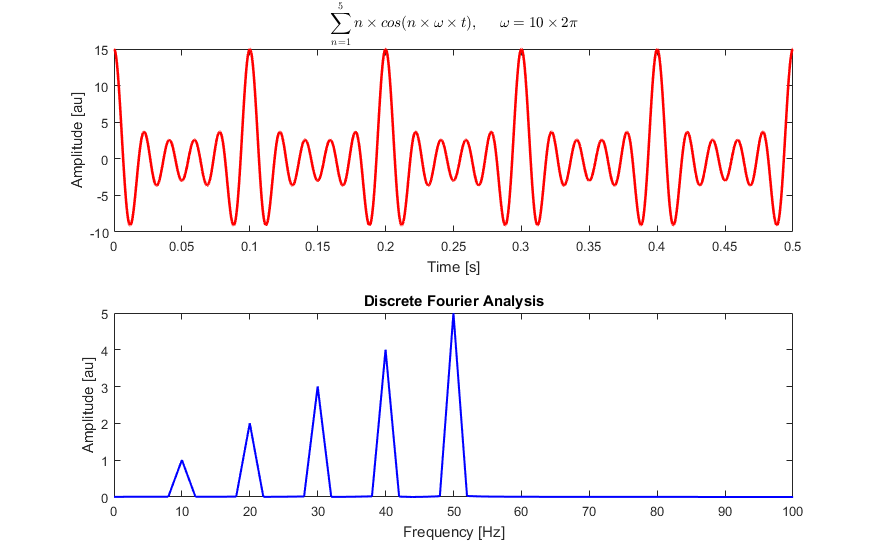

Here a discrete Fourier analysis of a sum of cosine waves at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 Hz:

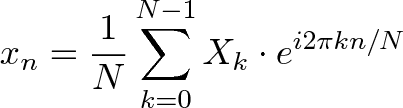

The Fourier Transform is one of deepest insights ever made. Unfortunately, the meaning is buried within dense equations:

and

Rather than jumping into the symbols, let's experience the key idea firsthand. Here's a plain-English metaphor:

- What does the Fourier Transform do? Given a smoothie, it finds the recipe.

- How? Run the smoothie through filters to extract each ingredient.

- Why? Recipes are easier to analyze, compare, and modify than the smoothie itself.

- How do we get the smoothie back? Blend the ingredients.

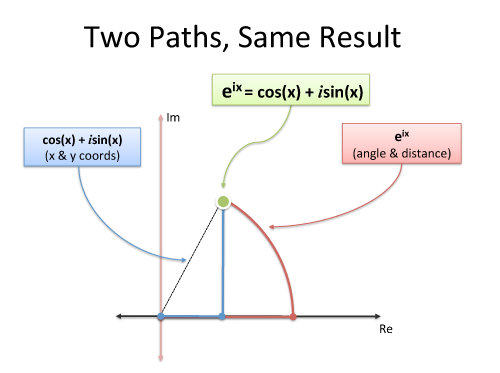

Think With Circles, Not Just Sinusoids

The Fourier Transform is about circular paths (not 1-d sinusoids) and Euler's formula is a clever way to generate one:

Must we use imaginary exponents to move in a circle? Nope. But it's convenient and compact. And sure, we can describe our path as coordinated motion in two dimensions (real and imaginary), but don't forget the big picture: we're just moving in a circle.

Discovering The Full Transform

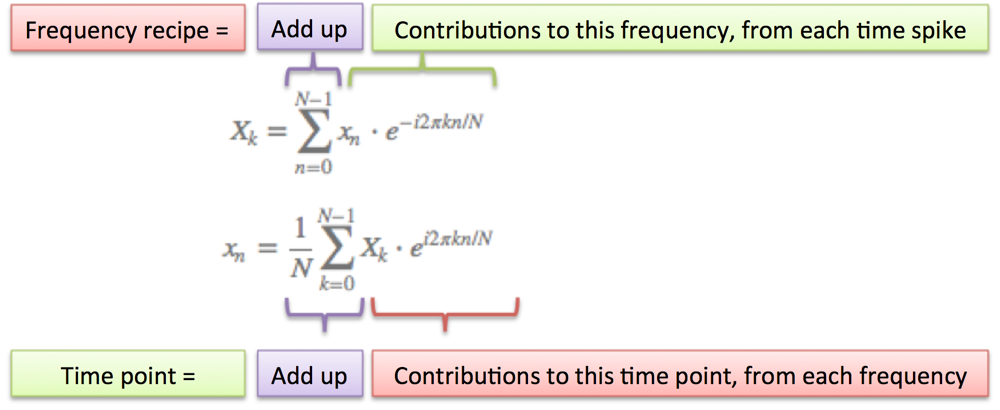

The big insight: our signal is just a bunch of time spikes! If we merge the recipes for each time spike, we should get the recipe for the full signal.

The Fourier Transform builds the recipe frequency-by-frequency:

A few notes:

- N = number of time samples we have

- n = current sample we're considering (0 ... N-1)

- xn = value of the signal at time n

- k = current frequency we're considering (0 Hertz up to N-1 Hertz)

- Xk = amount of frequency k in the signal (amplitude and phase, a complex number)

- The 1/N factor is usually moved to the reverse transform (going from frequencies back to time). This is allowed, though I prefer 1/N in the forward transform since it gives the actual sizes for the time spikes. You can get wild and even use 1/sqrt(N) on both transforms (going forward and back creates the 1/N factor).

- n/N is the percent of the time we've gone through. 2 * pi * k is our speed in radians / sec. e^-ix is our backwards-moving circular path. The combination is how far we've moved, for this speed and time.

- The raw equations for the Fourier Transform just say "add the complex numbers". Many programming languages cannot handle complex numbers directly, so you convert everything to rectangular coordinates and add those.

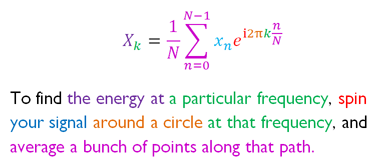

Stuart Riffle has a great interpretation of the Fourier Transform: