A computer that runs multiple processes or threads needs a away to handle what process will run at a time. Since one core can only handle one actual process at a time, the operating system switches between many processes multiple times a second. This is the work of the scheduler.

The policy that the scheduler follow is called a scheduling algorithm.

All algorithms want to fulfill these goals:

- Fairness - each process should have a fair share of the CPU

- Policy enforcement - stated policies should be carried out

- Balance - keep all parts of the system busy

When the schedule replaces the current process, it's called a process switch or context switch. All the registers of the CPU has to be saved and replaced with values from the process to run. This takes some time and is therefore expensive.

There are typically two types of processes: CPU-bound and I/O-bound. CPU-bound processes typically use all of their time with the CPU carrying out instructions. I/O-bound processes typically use the CPU for a bit and then go on to wait for I/O.

AS CPUs get faster, they can get more done quickly. Therefore processes tend to get more and more I/O-bound (they wait for I/O).

A non-preemptive scheduling algorithm allows a process to run until it blocks (I/O, waiting for another process, leaves voluntarily etc.). All scheduling calculations are done between running processes. Only switches context when it's logical / necessary.

A preemptive algorithm lets a process run for a fixed maximum amount of time. If the process is running at the end of the time, it is suspended and the scheduler chooses what process to switch to. A preemptive algorithm requires a clock interrupt. The scheduling calculations are done each clock interrupt. Switches context often.

Batch algorithms are still used at banks, insurance companies, research institutes etc. for payroll, accounts, inventory and calculations. The method simply works by configuring what processes to run and then leave everything up to the OS. They may use a non-preemptive algorithm or a preemptive with a long maximum time.

Main goals:

- Throughput - maximize jobs per hour

- Turnaround time - minimize time between submission and termination

- CPU utilization - keep the CPU busy all the time

Throughput is the number of jobs per hour.

Turnaround time the average time between a process has been submitted and completed

A simple non-preemptive algorithm. Processes are assigned to the CPU in the order that they are requested.

Another non-preemptive algorithm. Processes are assigned to the CPU in order of their time to complete, the shortest job first. All jobs must be available at the start of the scheduling for the algorithm to be optimal.

A preemptive version of Shortest Job First. The scheduler always choses the process with the least amount of time left.

Interactive algorithms are mostly used in servers and PCs. The use of a preemptive algorithm is essential to prevent any process to hogg all resources. Interactive algorithms always allow for user intervention. A general purpose algorithm.

Main goals:

- Response time - respond to requests quickly

- Proportionality - meet users' expectations

Response time is the time between issuing a command and getting the result

Proportionality is the term to describe how much time a user expects a process to take. They may allow a big file upload to take long, but not opening a simple text file.

An old, simple and fair preemptive algorithm. One of the most used algorithms. Each process is assigned a time interval called quantum. A process is allowed to run during their quantum. If a process is finished before the quantum, the next process is run. Implemented using a list of processes. New processes are put at the end. We can increase the quantum to lower the percentage of time used for context switching. If the quantum is 3ms and context switching is 1ms, the context switching "wastes" 20% of the CPU time. A shorter quantum, however increases the responsiveness of the system for the end user.

$- $No priority.

Based on Round-Robin. The runnable process with the highest priority is run first. To stop the processes with the highest priority to run forever, the priority may be decreased every clock interrupt. Now both the quantum and the priority can be tuned for performance. The priority can either be static or dynamically changed.

This is basically what is used in both Windows and Linux.

Like priority scheduling but with seperate queues for each priority level.

Real-time algorithms are mostly used in robotics, embedded systems etc. A preemptive algorithm may not be necessary as processes are aware of time and know that they can't block for ever.

Main goals:

- Meeting deadlines - avoid loss of data

- Predictability - avoid quality degradation in media devices, for example

Hard real-time are systems where a deadline cannot be missed Soft real-time are systems where missing deadlines are undeseriable but possible

When a real-time task is scheduled, it must be in such a way that all deadlines are met.

Events in a real-time system may be periodic (occur at regular intervals) or aperiodic (occur unpredictably).

A real-time system is scheduable only if all events can be processed in time.

Old systems had no memory management system. Every application had direct access to linear, physical memory. This causes all sorts of problems (other programs can read/write to your memory, programs can write to the operating system's memory etc.).

Using an address space solves two issues: reallocation (a process can have its memory in different parts of the system) and protection (programs can't read or write to others' or the OS's data).

Examples of address spaces in the world are postal codes, phone numbers, IP addresses etc.

One early system revolved around using base and limit registers. Processes were loaded in to consecutive memory. The base and limit registers were set to the start and end of this address space. The only addresses the process could now use were those inside of the address space. Addresses were mapped to the address space (jmp 3 became jmp <base> + 3).

Unless a system got lots of memory available, it is impossible to have all processes in memory at a time. A simple algorithm to solve this is swapping. Each process is put into memory in its entirety. When it's been run for some time, the entire memory is written to disk and taken out of memory to make room for another process.

Virtual memory allows a process to run even though it may not be entirely in memory (missing some frames). When a frame needs to be allocated and there is no space left in memory, a frame is selected and written to disk. That frame can then be reused. This is the way to go if processes should be able to expand dynamically.

We need to be able to reference what frames are available. This is mainly done via two algorithms.

Each frame is assigned a bit. The bit is 0 if the frame is free and 1 if it is taken. The index of the bit in the bitmap can be multiplied by the frame size to get the frame address. A free frame is found by iterating over the bitmap until 0 is found.

A linked list is created where each node is stored in a unused frame. Each node points to the next node (frame). When a free frame is needed, the head of the list will point to the frame. The next element replaces the head.

###Virtual memory: paging

Paging is a commonly used method to provide virtual memory. Whenever an address is referenced (such as with mov ) the CPU sends the address to the Memory Management Unit, MMU, which takes the virtual address and maps it to a physical address together with the OS (see below). A system may be able to support more virtual addresses than there are actual addresses leading to the need for page replacemenet algorithms.

The virtual address space is divided into fixed-size units called pages. The actual physical memory the page is mapped to is called a frame. A common size for both is 4KB.

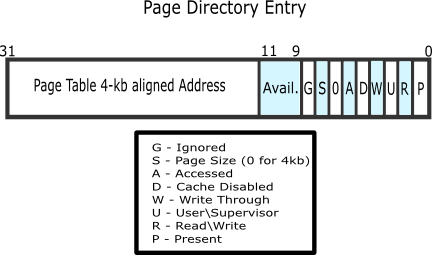

The top level structure is called a page directory. It is an array of 1024 page directory entries. Usually (32-bit systems) the first 22 bits of the page directory entry refers to a page table, the rest are flags such as whether the table is present (in memory) or not.

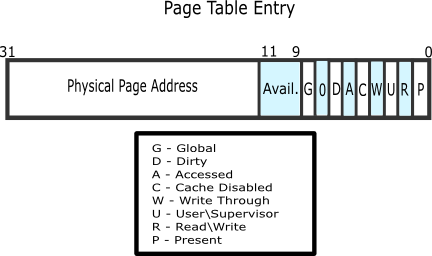

In a page table there are 1024 page table entries. Usually (32-bit systems) the first 22 bits of the page directory entry refers to a physical page (frame), the reset are flags just like with the table.

The mapping then goes like this:

The first 10 bits (offset) represent the index within the page that leads to the physical address. The next 10 bits (table) represent the index within the page table that leads to the entry, referencing the page the physical address is in. The last 12 bits represent the index in the page directory where one can find the reference to the page table.

Paging can be slow. On modern systems a TLB is used to speed up the process. A TLB is usually inside of the MMU and it caches information about pages so that each page will not have to be mapped through the OS. There are usually no more than 256 entries in the buffer.

The above-mentioned design is basically two-three levels deep. One can extend this scheme to allow for referencing of more memory. For example, each page table entry could point to another page table and so on.

When the MMU tries to map an address referencing a page that is not in memory, a page fault occurs. If the page is stored on disk, the OS should read it back into memory. If the page is near the stack of the process, one can allocate another page to automatically increase the stack. If the page simply does not exist, an error occurs.

If the memory is full when a frame is allocated, a page eviction algorithm needs to select a frame to store on disk and free.

Each page that is allocated is put into a list. The first page that has been allocated is the first page to be evicted.

Similar to FIFO. If the page flag R (referenced) is 0, the page is old and unused so it can safely be replaced immediately. If R is 1, the flag is cleared and put at the end of the list (as if it was newly allocated).

Similar to Second Chance. Improves the inefficency of moving around items in a list by using a circular list instead. The hand of the clock (head of the list) points to the oldest page.

Makes use of flags for pages. The flags are R (referenced) and M (modified). The flags are set by the hardware but must be reset by the OS.

When a process starts, the flags are reset by the OS. Every now and then (such as each tick-interrupt) the R flag is cleared. When a page fault occurs, the OS inspects all pages and put them into four categories:

Class 0:

When chosing a page to evict, the lower the class, the better.

Similar to NRU, but orders pages in the list to be able to reference the least recently used, which can be evicted.

To wait for page faults to occur before loading a process' pages to memory can waste unnecessary CPU time. Instead, the Working Set algorithm tries to identify what pages a process needs for execution - its Working Set. The general idea is to greatly reduce the page fault rate by loading required pages in beforehand (pre-paging).

A great improvement over WS that can be used in reality. Related to the Clock algorithm, but borrows ideas from the WS. Instead of only checking for the flag R, it also checks for an age towards a pre-determined value. When a page should be evicted, the hand of the clock is inspected.

If the flag R is set, unset it and move on. If R is 0 and the page's time of last use is greater than the threshold, the page is evicted. If R is 0 and the page's time of last use is less than the threshold, move on.

A file system tries to solve topics related to persistence (outlive the process), collaboration (multiple process can access data at once) and size (store loads of data). Presents an abstraction of the underlaying physical system.

An abstraction of data storage typically used is a file. A file usually has a name and an extension. Typically the OS does not care about either - it simply stores the data.

There are typically three ways to structure data on the disk. Either the filesystem only sees bytes on the disk, records (collection of bytes) or a tree structure. Both Windows and UNIX use the first approach (byte).

Using bytes give the programs maximum flexibility. Using a tree provides a rich representation of a file structure.

Early file systems only supported sequential access - one could only read bytes in order. Modern file systems support random access where bytes can be read in any order. Random access is essential for databases (read / write to a specific slot fast without going through the entire database). A program can either specify where to read from or seek up to the point where reading should start. The latter, sequential way, is used by Windows and UNIX.

To ensure portability (files can be moved from one system to another and back), most systems use raw byte streams.

The disk is layed out as follows.

The Master Boot Record (MBR) lies in the start of the disk, referencing where partitions are and how big they are. A partition is a part of the disk used to isolate operating systems. A partition starts with a boot block (the actual OS) and a superblock (stores necessary information about the file system). Typically there are also some sort of free space management, storage for i-nodes etc.

The physical data sections on a disk are called sectors (512 or so bytes). Usually, an OS orders multiple sectors together to form a block (4096 or so bytes). The OS never sees the actual sectors, it only cares about the blocks. A block size that is too large means that we're wasting data, a block size that is too small means that we're wasting time.

The simplest way to store a file is to have it in continuous blocks of data. Then the start can be referenced and the end can be marked as the end. The file system can then simply read the file sequentially. When files are removed, empty block are left and this will lead to fragmentation of the disk. The contiguous system is however really simple and typically fast.

A more advanced way to store files is to use linked lists. The first data block points to the next and so on. This can defeat fragmentation but may reduce speed as data blocks are scattered throughout the disk.

One way to use some of the features of both previously mentioned methods is to store the linked list in memory, in a File Allocation Table (FAT) (see below).

This method allows for easier random-access and improves overall speed of finding files and their blocks. The issue, however, is that the table grows with the disk. A modern disk would require gigabytes of memory.

This method was used in the MS-DOS OS as FAT-16. For Windows 98 the system was extended to FAT-32. There is still support in modern Windows for FAT-32.

I-nodes, or index nodes, works by keeping track of what blocks to associate with which file. The big advantage over FAT is that only the i-node of the open file needs to be stored in memory. However, this may lead to greater disk usage / waiting time when i-nodes need to be read from disk.

Below is a i-node structure from UNIX.

An i-node stores file attributes (could include file name), about 5 addresses to data blocks and addresses to other i-nodes: single indirect - one i-node referencing blocks, double indirect - one i-node referencing two i-nodes referencing blocks and triple indirect - one i-node referencing two i-nodes referencing two i-nodes referencing blocks.

I-nodes can theoretically handle unlimited file systems in terms of file system size and file size.

Windows NTFS uses a similar idea to i-nodes.

LFS works by caching all disk changes and writing as much as possible during a single instance, minimizing seek and wait time. A record contains a log summary, identifying what is found within the record, i-nodes, data blocks and so on. The idea is to use the full bandwidth of the disk.

The file system works well for large read and writes. Not widely used. Incompatible with other file systems.

The basic idea is to keep track of what a file is about to do so that in the event of a system crash, there's a log of what to do. This sort of file system is widely used (NTFS, ext3). The log items must be idempotent, meaning that the action can be repeated as many times as necessary without causing harm.

A VFS simply abstracts one or more file systems into one. The user sees one file system, but the VFS may actually use several different systems. Windows use different partitions for different file systems, UNIX file systems are usually backwards compatible.